Web Attack Investigation: Live Lab Environment & Log Analysis

Today is January 28th, 2025, and I've just completed the "Investigate a Web Attack," course found on the Let's Defend SOC Analyst learning path.

The course is set up as a virtual machine. Upon accessing the machine, I had to find the log files, open them, and begin assessing them as I looked through them for clues. In the end, I had 7 questions to answer correctly in order to move on to the next course. In this blog post, I'm going to be covering my assessment, how I arrived at my assessment, and my answers to the questions.

Logging into the lab environment:

The virtual machine with access log.

Directory and file extension brute forcing:

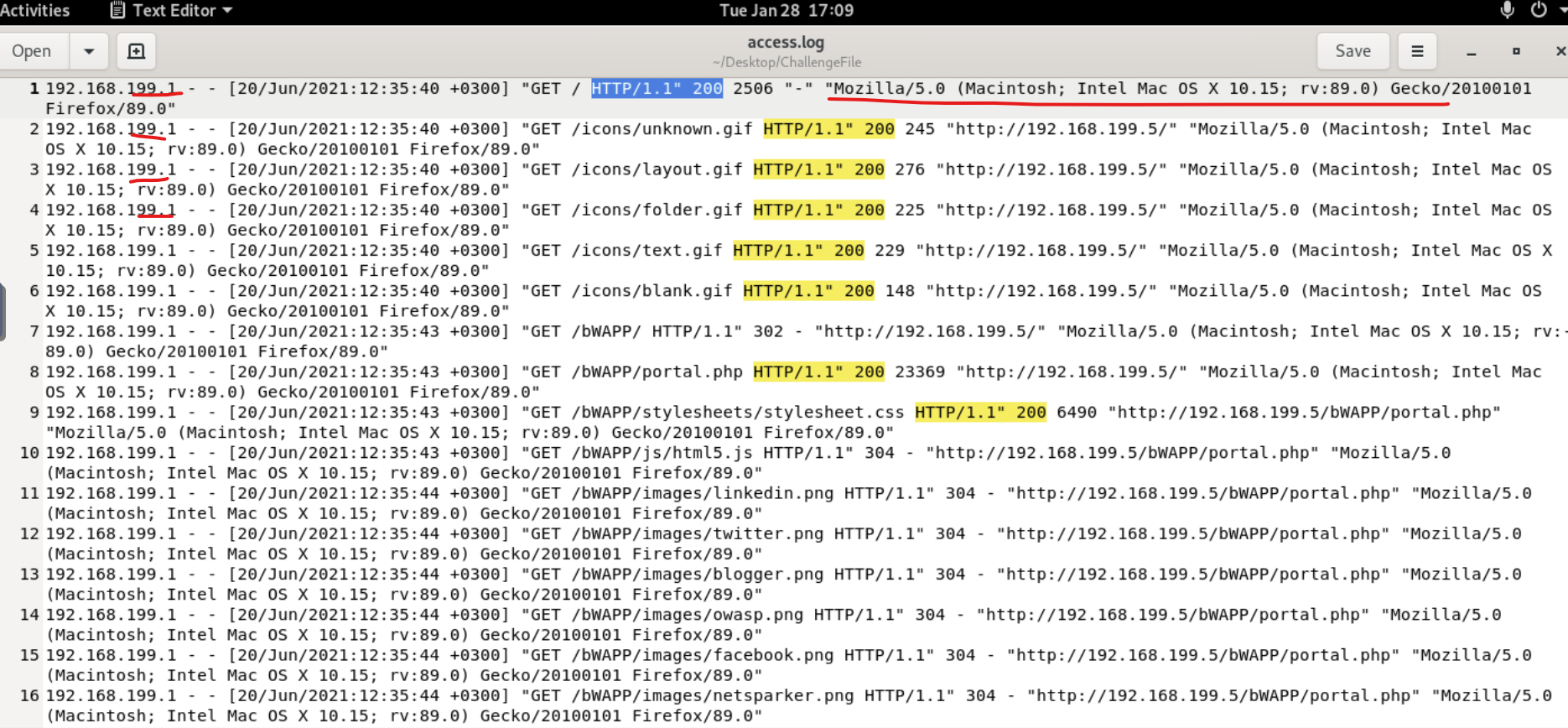

Upon my first opening of the logs, I was met with this:

Nothing suspicious yet. Just taking note of the user 192.168.199.1 - both the IP and the user-agent telling me which browser and what versions the individual is using. If you look at the the GET requests below the first one, you can see that the response is successful (200) and takes them to the IP 192.168.199.5 which suggests there is a redirection, forwarding, or proxying happening in the network. Nothing too crazy yet, just making note of what I see. The 200 codes were highlighted because I was filtering my results based on successful responses to see which resources were successfully accessed by users. Let's move on.

Nikto: A web vulnerability scanning tool

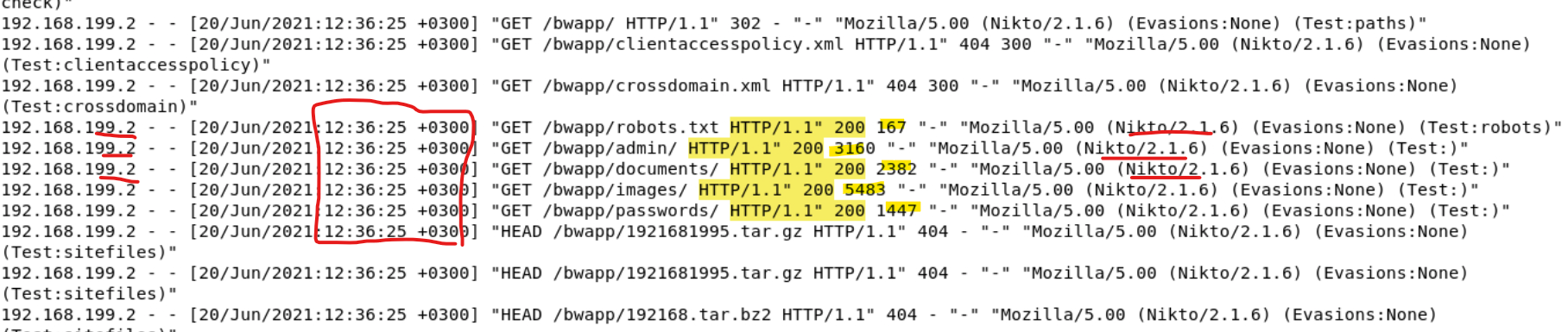

Notice that, at line 30, a new device on the same network is now logging activity. 192.168.199.2. The very first request is a HEAD request that essentially checks whether a resource exists or not without actually fetching it for the requestor. And look at the user-agent, where you'll find the name "Nikto/2.1.6)". Nikto is a freeware command-line vulnerability scanner. A tool used to assess and find vulnerabilities. This is telling in itself. On one hand, if the tool is authorized to be used to test a site's vulnerability, this could be an individual who works for the company (same network - different device - see IP address) doing some management. On the other hand, however, if this is not an authorized vulnerability scan being used for assessing the company's security, it could mean that a potential attacker is scanning for vulnerabilities to do some reconnaissance and find the best possible attack vector.

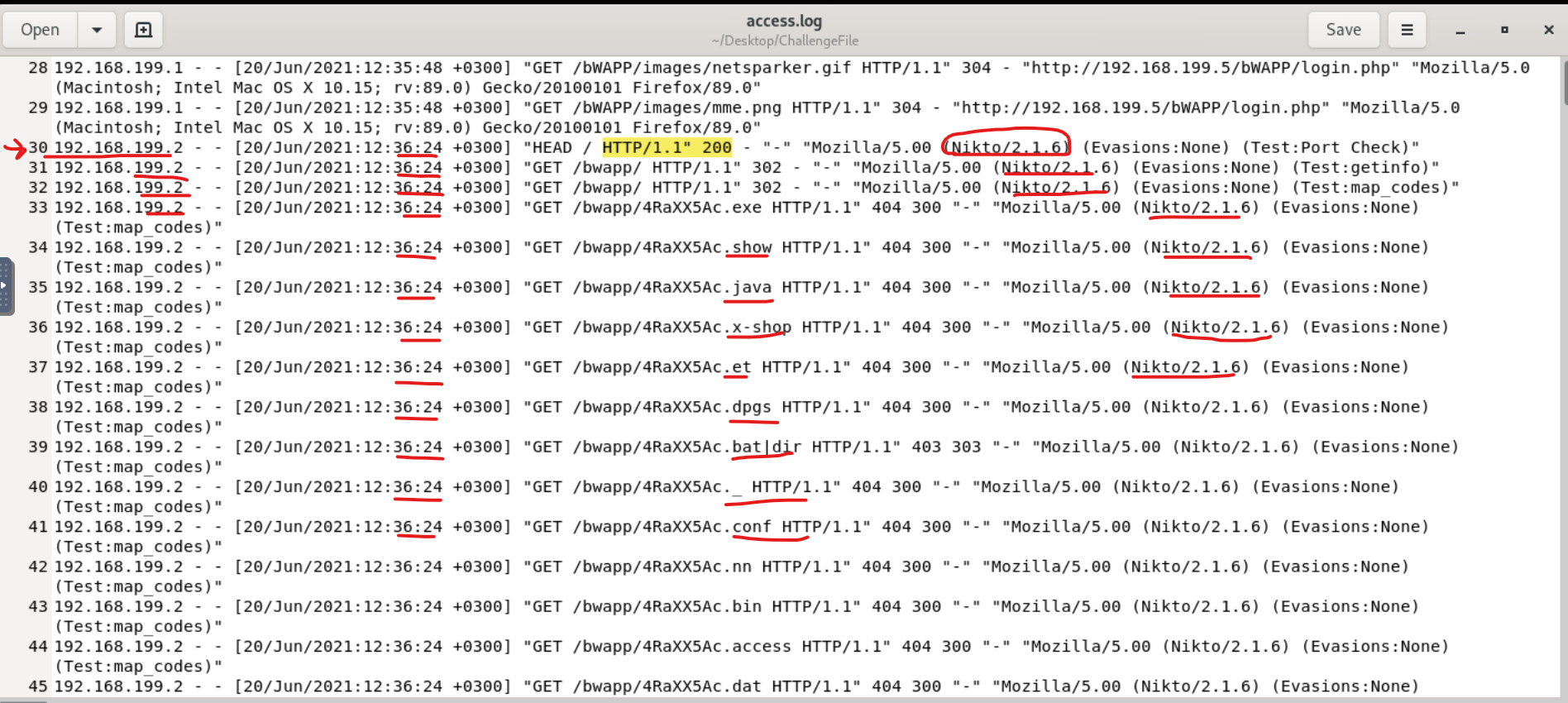

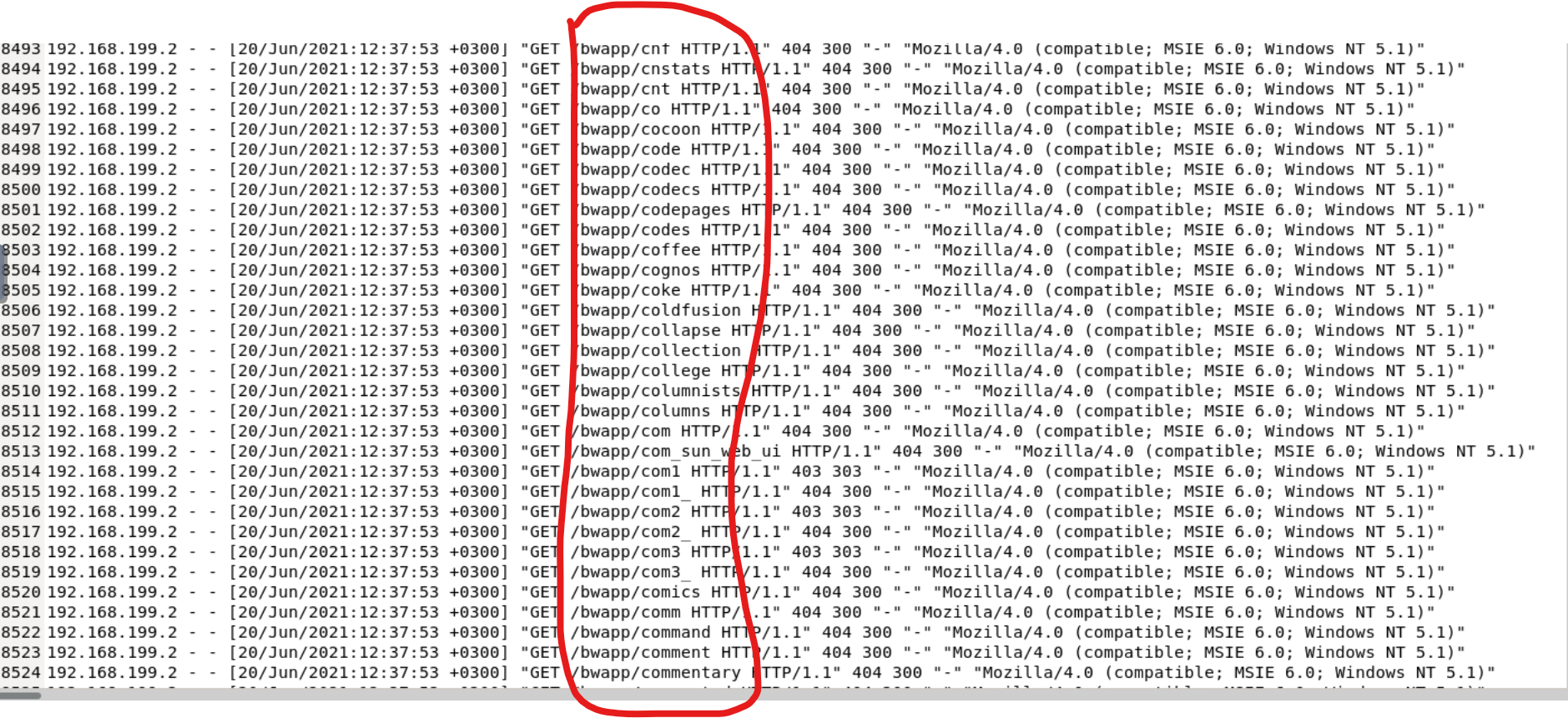

Immediately, we can see that some kind of testing is being done, whether malicious or not we do not know. But looking at the timestamps and tool name in the user agent, we can see that dozens of requests are being made per second, much faster than any human could produce. Examining the GET requests also shows WHAT is being tested. The "/bwapp" directory is having a brute force attack done on it. common file extensions and names are being rapidly iterated and attached to the end of folders, resulting in either a 404 (bad request), redirect (300, 302), or 200 (success). The software runs through a large list of common payloads and file names and processes multiple attempts per second. Below is an example of more brute forcing on directories:

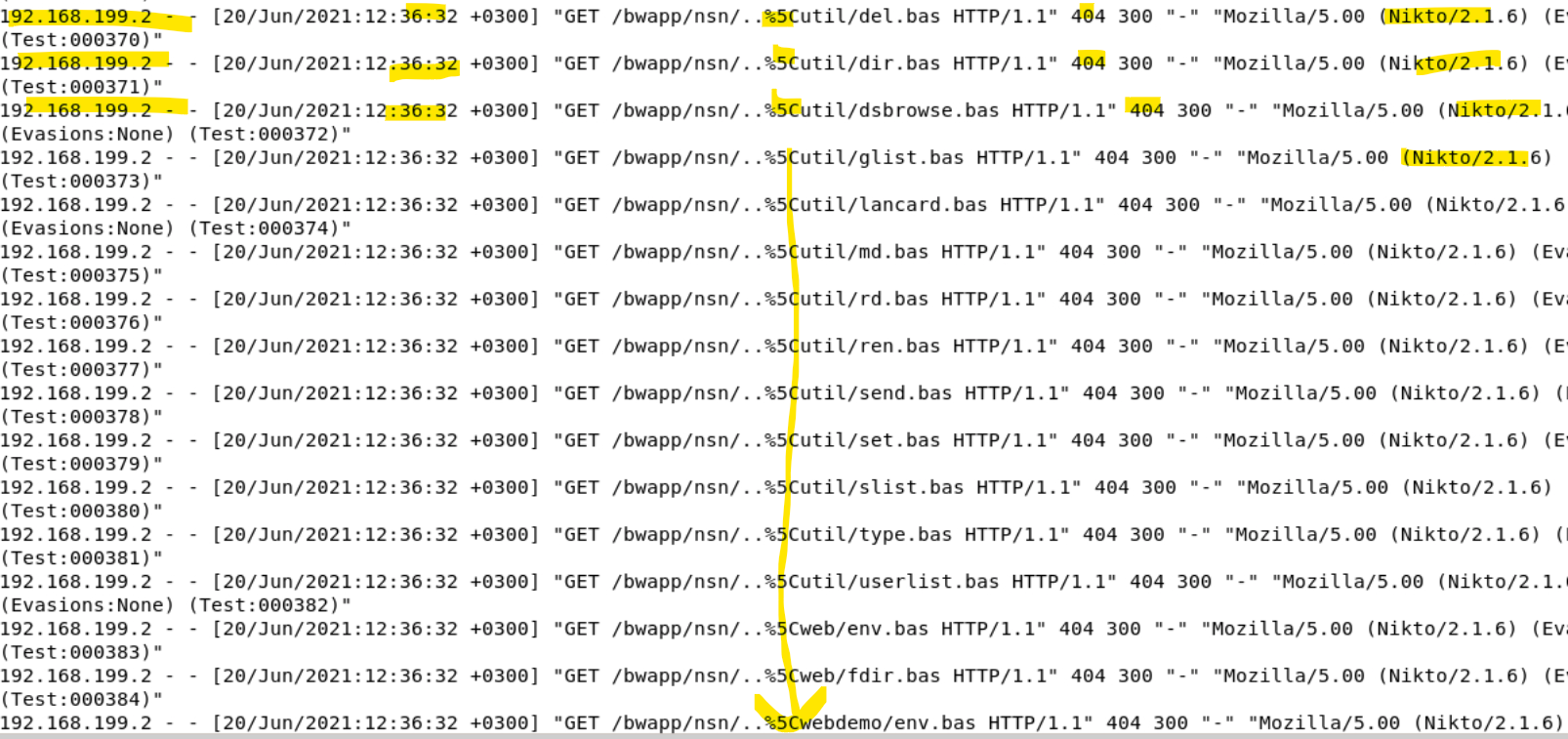

More brute forcing, trying every combination it can until something sticks. You can see words being iterated and fed through an algorithm, concatenated to the bwapp folder structure, all of them returning a 404 error for not being found. It's still extremely suspicious if no company order has been established for routine testing.

In this snippet, we can actually see some successful (200) responses with large response sizes, which would give an attacker information like knowledge that these folders exists and were successfully retrieved. One of the folders is even called passwords, which seems like a huge vulnerability and a potentially serious problem.

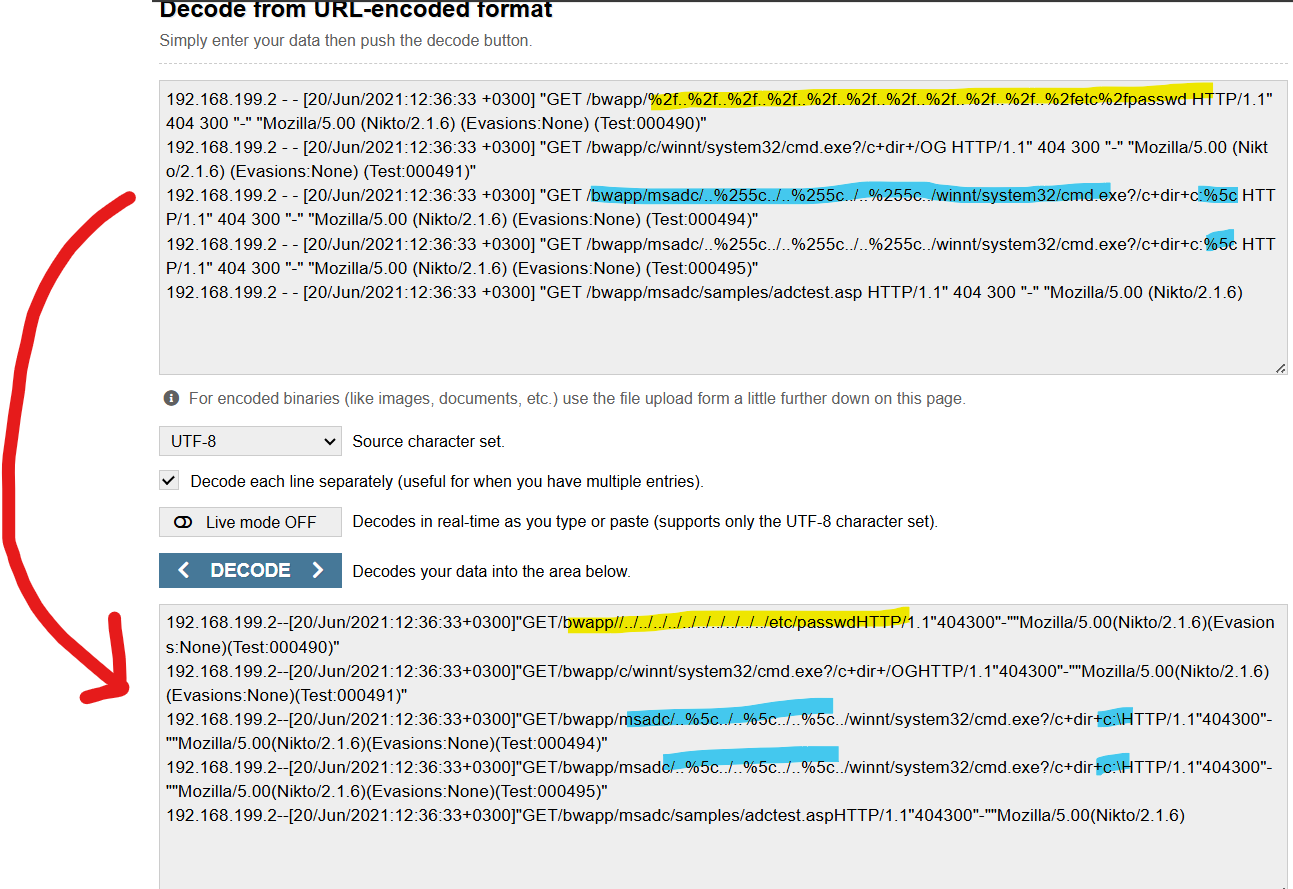

Encoded characters being used to hide attempts to traverse directories.

Another example found in a log after being decoded:

In a previous blog post, I wrote about directory traversal and how often times it is called the "dot-dot-slash" attack because of the "../" commonly used to move through directories by attackers. Here we can see it appears that directory traversal attempts were made, still using Nikto. Now, when plugging the log into a decoder, it becomes more apparent that directory traversal is indeed being used. Look closely and you can see that the attacker attempts to navigate the file structure "etc/passwd" again, harmful if successfully able to retrieve data.

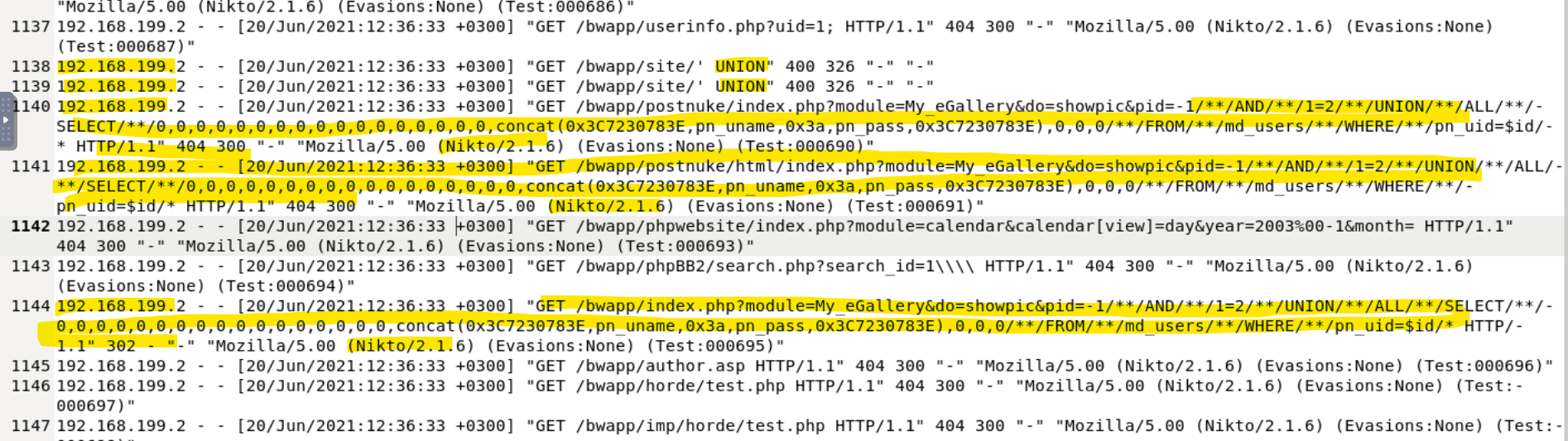

SQL injection

As I continue down the logs looking at the long list of 404s and more brute forcing, I come across something different that does not look like brute forcing. I recognize the terminology and remember learning about this in the first few lessons of my SOC analyst learning path. I immediately recognized it as an attempt at SQL injection, based on the syntax and commenting out of code. I was glad to recognize it because I felt my skills in recognition growing. Look at how noticeably different SQL injection looks on the system logs:

Looking closely, you can see the key terms like AND, UNION, SELECT, concat, /**/, FROM, WHERE. This was definitely SQL injection. Luckily the result was a 404, so it was unsuccessful. At this point we still don't have the context that would determine if this testing was intentional or a threat actor.

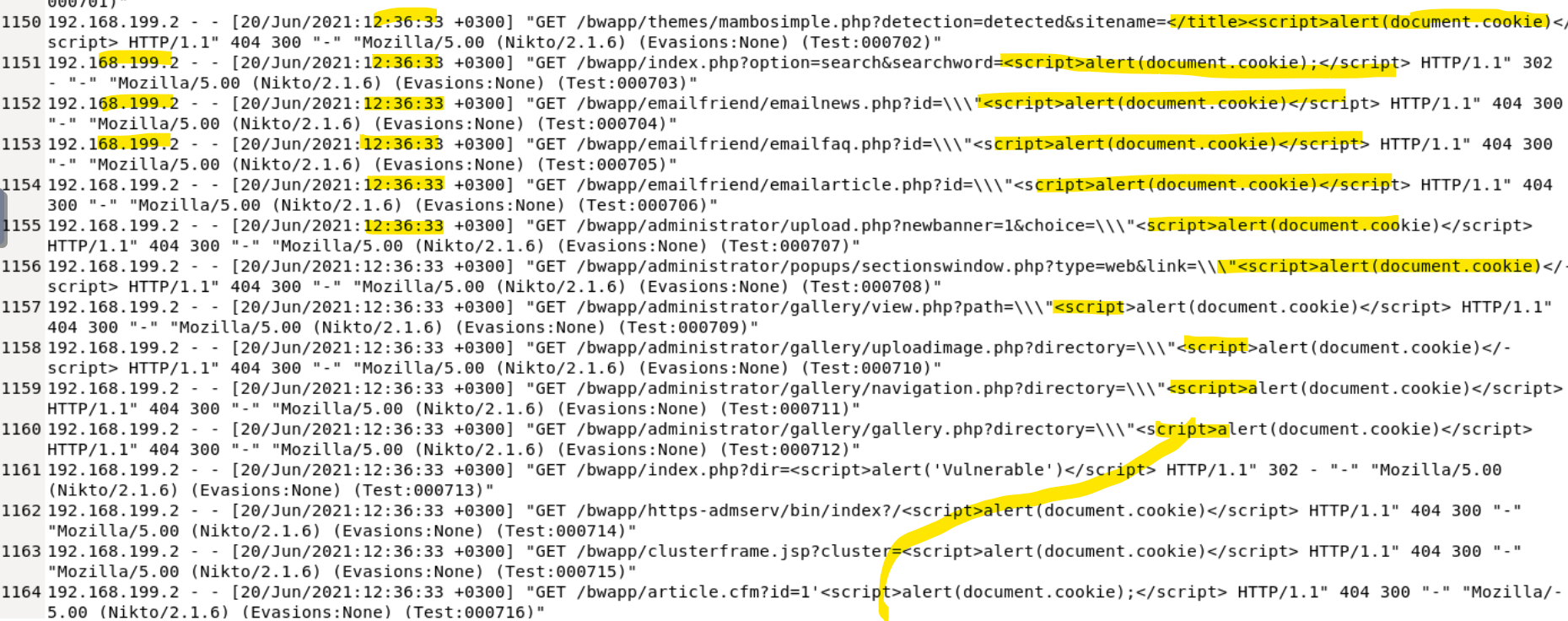

Code Injection

In the logs above, we can see that XXS, or cross-site scripting is being used, by which an attacker attempts to inject code, usually JavaScript based, in order for the code to be executed. In this case, the code that is executed would pop an alert up in the window. The content of that alert would display cookie information relative to the document. Cookies are stored as strings in the format key=value. If multiple cookies exist, they are separated by semicolons and a space (; ). For example: "user=JohnDoe; session_id=abc123; theme=dark"

If session cookies are stolen, they can allow an attacker to impersonate a legitimate user! All of the XXS attacks resulted in a 404 error except one (bottom picture) in which the script tag was nested in encoded characters. This would produce an alert that said "Vulnerable" on it, which is either telling an attacker that a particular vector is possible there, or telling a scheduled tester that a vulnerability exists here and needs to be mitigated.

So far, all of these "attacks" have been carried out by the same user, who is also on the same network as the first user on the first page. Either this is an inside job, or there is some kind of company vulnerability testing. Let's continue:

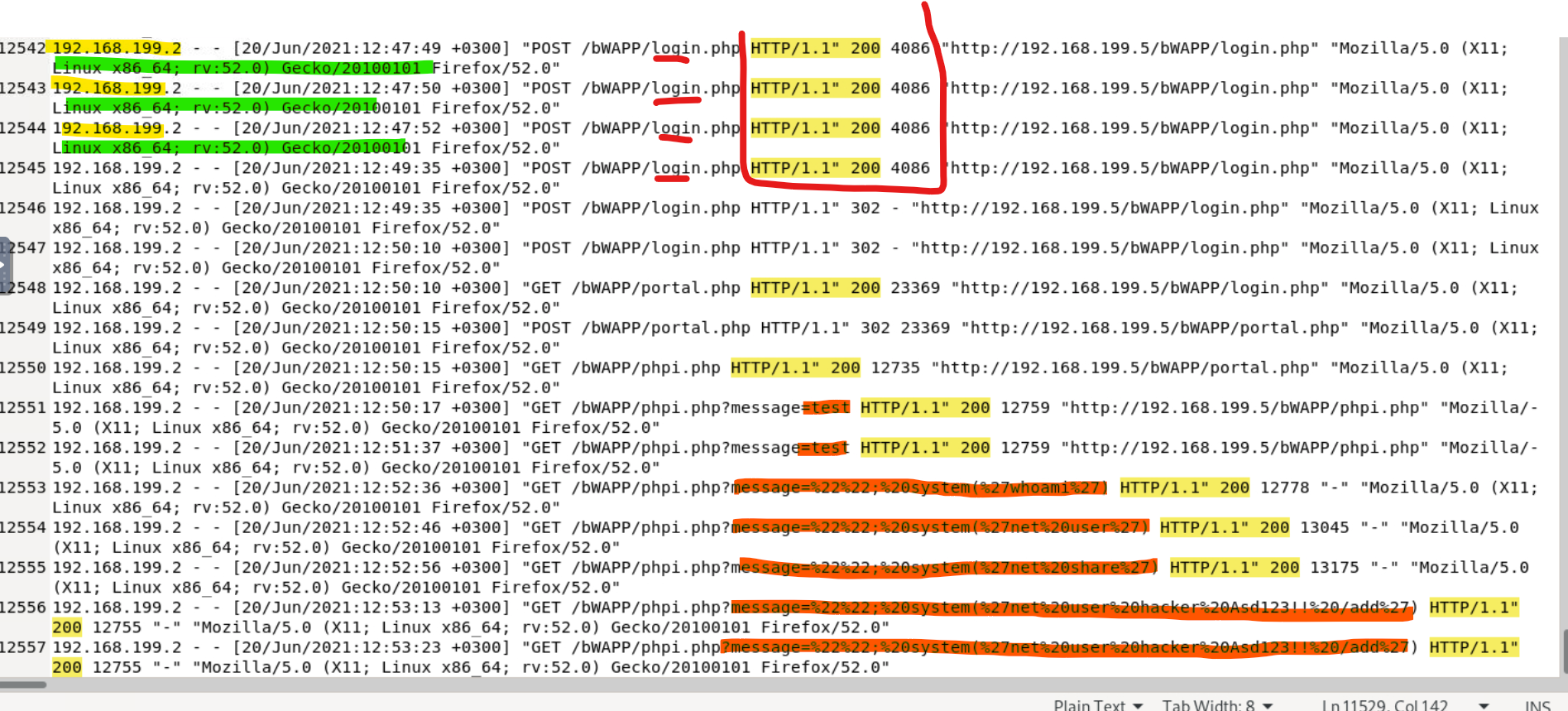

Command Injection

Interestingly, as we approach the final attack type and end of the logs, the IP address does not change, however the user-agent does. This time the Nikto is gone, suggesting the tool usage has stopped, however there is now a Linux system being used running Firefox. Again, not enough data exists to inquire as to whether internal company testing was being done or if the threat actor actually worked at the company, but it does appear that the devices are all working on the same network. The login attempts here are successful, but they are also more spread out in time, again suggesting an actual human user is determining the machine's traffic.

On lines 12551 and 12552, the "message" parameter is queried with "test" with successful responses and large relative byte sizes suggesting successful connection. After testing, we see immediate command injection using encoded characters to execute the command "whoami", which is used to display the username of the current user who is executing the command. It answers the question, "Who am I logged in as?" It allows an attacker to know what device they are on.

From there, more command injection occurs querying the message parameter, this time entering:

%27net%20user%20hacker%20asd123!!%20/add%27

(remove encoding)

'net user hacker asd123!! /add'

Executing this command would allow the attacker to add themselves as a legitimate user on the system. Not only that, but its an example of persistency which is a method used by attackers to maintain connection or permanence in the targeted system. If you notice, both of those logs ended with a 200 response suggesting that the attacker was successful, creating himself as a user to stay connected, potentially causing tons of damage in the future.

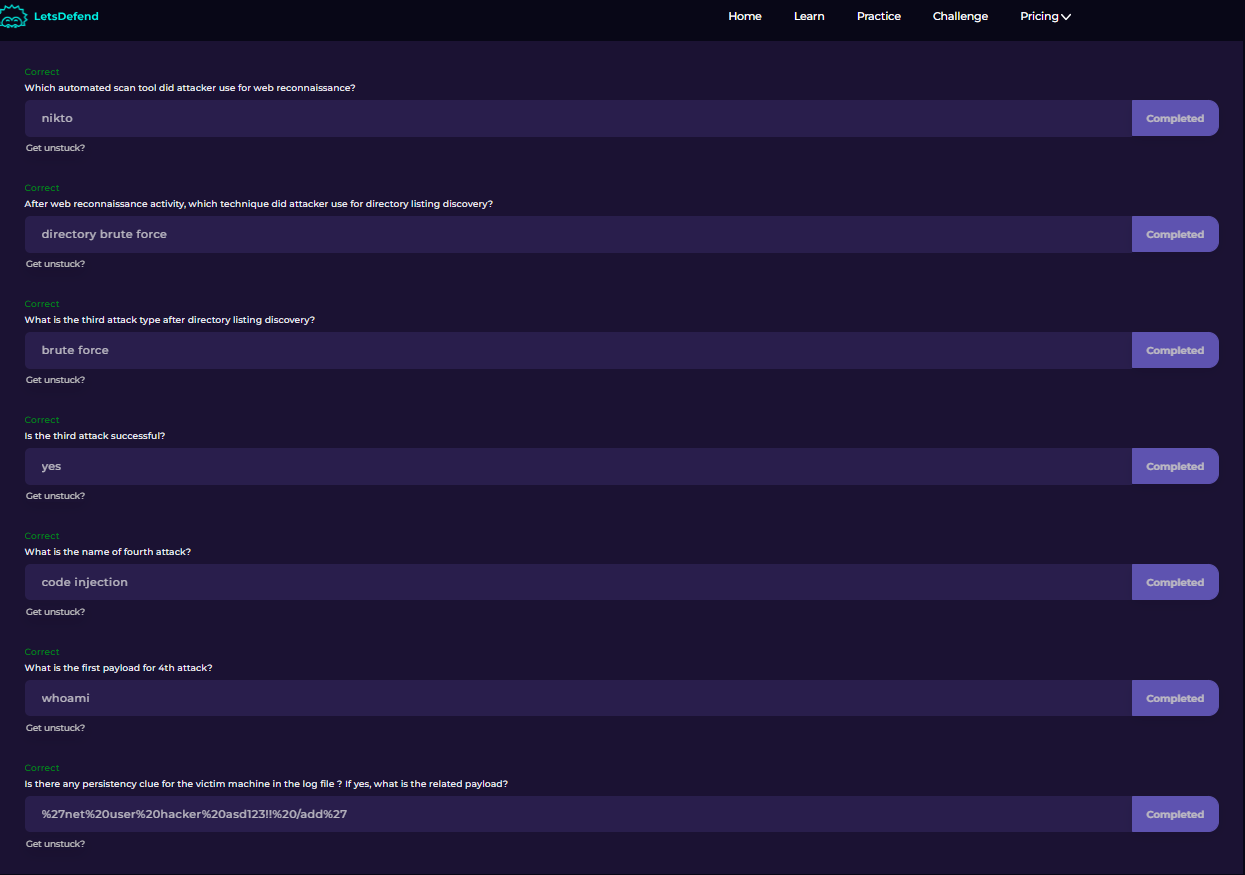

Questions and Answers

Each of these questions are answered in this blog post, but I will quickly recap here:

1. Which tool was used? Nikto - check the user-agent

2. After reconnaissance, which technique was used? We saw that after some intial small probing, the attacker began to use directory brute force to query different directories and file extensions.

3. The third attack type after directory listing discovery is again brute force. I have show this in the picture above. Once brute force methods discovered a vulnerable directory, brute force could be used additionally to query files in the directory using common names and words.

4. Successful? Yes. See the 200 response codes found under the directory traversal section. Even managed to successfully access a password folder.

5. The fourth attack was code injection - also known as XXS or cross-site scripting.

6. The payload can be found on the image under the Command Injection section. After testing the message parameter, the payload was then sent encoded to the server through the message parameter.

7. The persistency clue was the final payload and log entries found on the logs themselves. Decoded, the payload executes a command that adds the attacker as a new user, helping them stay on the target machine and gain further access. This is an example of persistency.

Thank you for reading, I hope this helped!